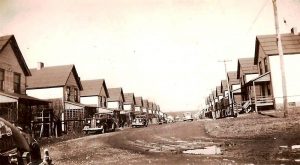

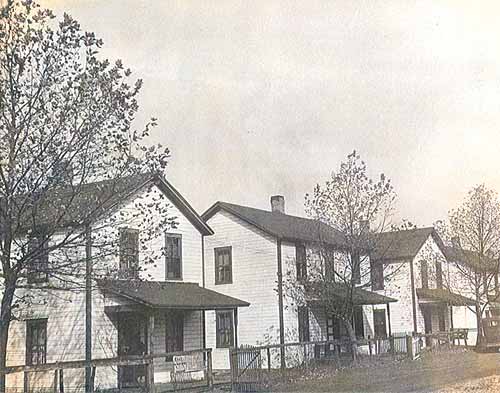

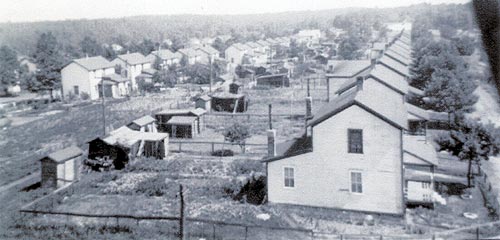

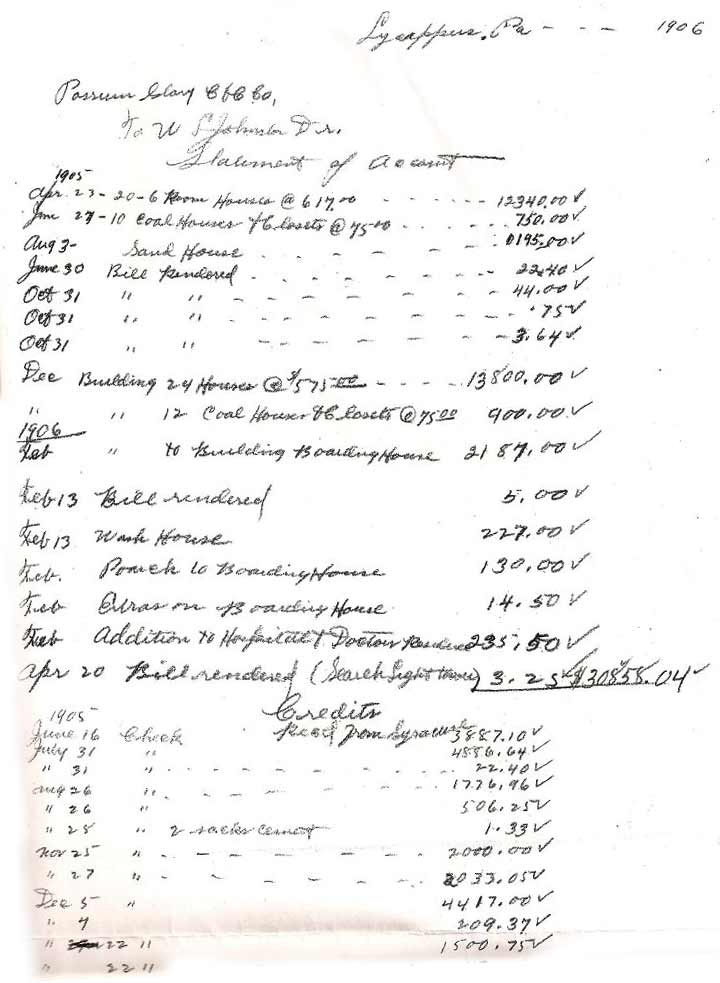

Housing for the coal miners in Heilwood had many similarities to the housing in other bituminous mining areas of Western Pennsylvania in the early 1900s. Designed and constructed for the most part by mine engineers rather than architects, the housing was of a similar plan and type. Arranged along rectangular lines of survey, the houses presented a dull, uniform appearance, devoid of trees and natural vegetation. Streets and alleys were open dirt roads and sidewalks were rare. D. Lynne Morehead laid out the town of Heilwood, while J. P. Kennedy of Blairsville, Harry Clark of Glen Campbell, and W. L. Johnson of Lycippus, plus a few others, would construct the homes.

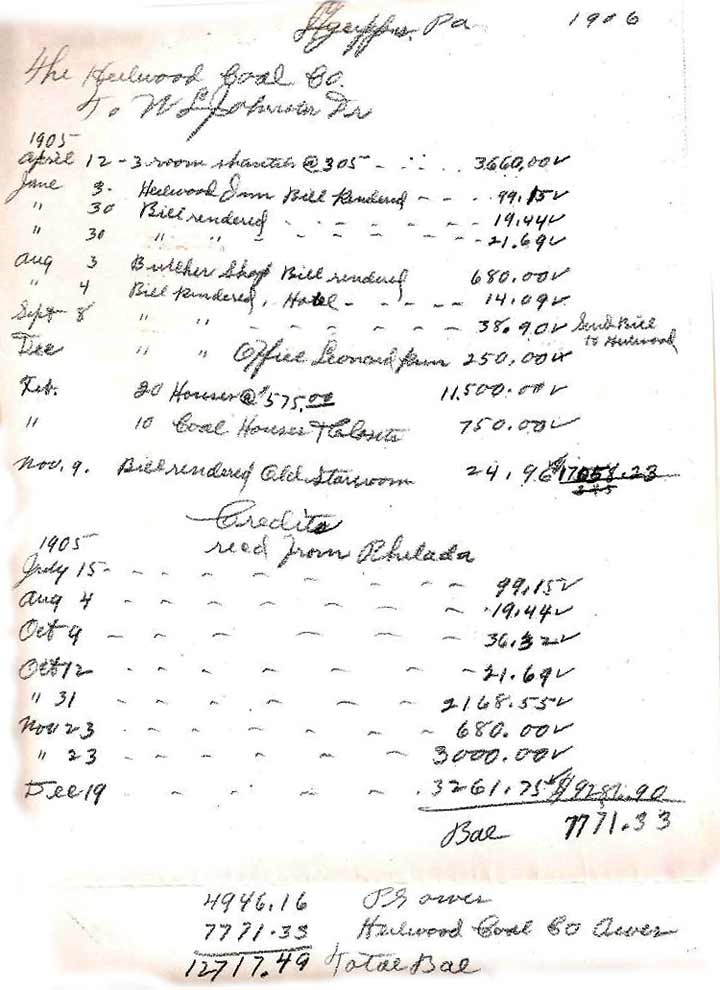

The standard miner’s house was a plain (Vernacular Homestead style), two-story, probably balloon/frame construction, with an average of 4-6 rooms, and built as economically as possible (a four-room house cost $575, while a six-room house cost $617). For coal mine operators, keeping the cost of building the houses low was very important – since there was no way to predict the lifespan of the mine, the town was viewed as a possible temporary settlement, to be abandoned when the mines were worked out.

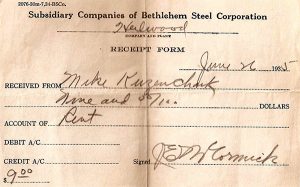

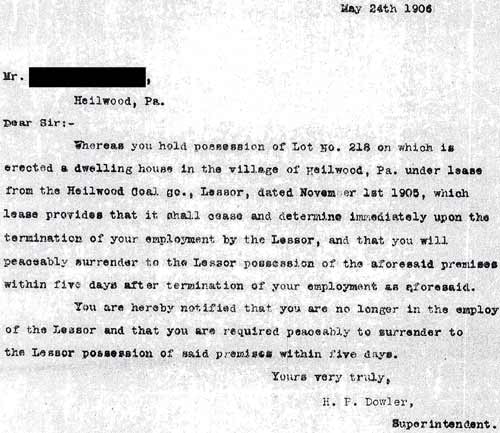

The miners rented their homes, probably paying as much as $1 to $2.50 for each room per month. There were written leases, but they only covered a miner’s period of employment. The death of the miner or the termination of employment meant that the miner only had five days to vacate the premises or face court action (see letter at bottom of page).

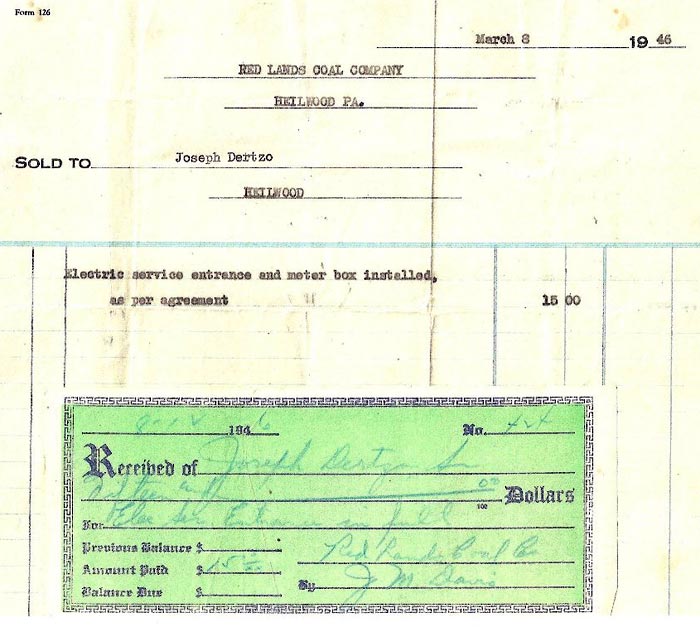

With no basement, the homes were heated by a single coal/wood-fired stove in the kitchen, with floor grates that opened into the second floor for heat. In some cases, additional heaters of some type were utilized to supplement the stove in the kitchen. Running water and electricity were usually provided for free, but “house coal” had to be ordered and paid for by the miners. Each house did have some room for a yard and vegetable garden (see photos).

In most cases, indoor plumbing was non-existent – at least in the typical coal miner’s home. Privies were usually located at the back end of the lot, next to the alley and alongside the coal shanty or neighbor’s privy (and in some instances, privies were shared by neighbors!). “Honey dippers” would pump the contents of the underground holding tank on a regular basis, and spread a fresh coat of white lime to sterilize the area. This turned the alleys into a checkerboard of brown and white.

Despite the lack of plumbing, it should be noted that at a February 1913 Sanitary Engineer’s Meeting in held Philadelphia, Herbert Snow, then the Chief Engineer of the Pennsylvania State Department of Health, stated that “Heilwood is the most sanitary mining town in Pennsylvania.”

SELLING THE HOUSES TO THE TOWNSPEOPLE

In 1943, the Monroe Coal Mining Company, a subsidiary of the J.H. Weaver Company of Philadelphia, purchased over 16,000 acres of coal lands in Indiana and Cambria Counties from the Bethlehem-Cuba Iron Mines Company (a subsidiary of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation). In addition, the Monroe Coal Mining Company acquired 2,000 acres of surface land in Indiana County, including the entire towns of Glenside (42 houses), Mentcle (40 single-20 double houses, and Heilwood (136 houses). It should be noted that the Redlands Coal Company (a different subsidiary of the J. H. Weaver Company) had been leasing these properties since 1940.

Within a week of its purchase, the Monroe Coal Company informed the current residents that their homes would be sold, and that residents were welcome to buy them. No official reason for the decision to sell the homes was ever made by the company, but the rumor at the time was that it was simply too expensive to adequately update all of the homes in order to continue to rent them, and therefore the most economical solution was to sell them off.

In addition to the homes in each town, vacant lots and businesses were also offered to anyone who could afford to purchase them, either on a payment schedule or as a lump sum. The Monroe Coal Company also made the existing churchbuildings and properties available to the congregations for a nominal fee.

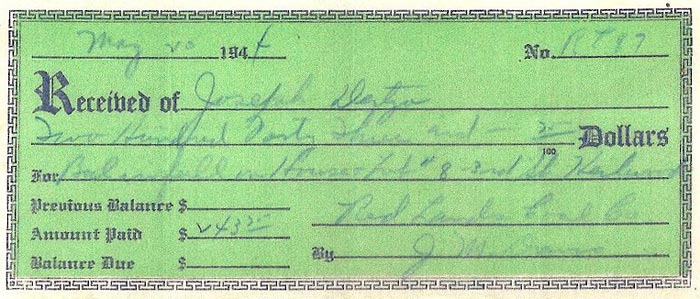

By June of 1944, residents of Heilwood began purchasing their current homes and/or various vacant lots around town.

Shortly after purchasing their homes, many of the new homeowners began the process of installing indoor plumbing and eliminating the backyard outhouses. Many of the new homeowners also decided to dig out basements under their house, so that they could place a central heating furnace rather than relying on the kitchen or parlor stove to heat the home (see photo at left). One anecdote from this time – while digging out the basement, one family became a little overzealous in their use of dynamite, and the resulting explosion nearly destroyed their entire home!

MAINTENANCE OF THE HOUSES & BUILDINGS

When all of the houses in Heilwood were rentals, the families living in them had to rely on the coal company for maintenance of the buildings. The coal company employed a crew of at least five to eight men, who were responsible for all carpentry, painting, plumbing, heating, installation of electrical poles, and whatever else needed to be done (see photo). The earliest mention of major repairs to the houses being carried out by the coal company’s maintenance crew was in August 1915, when new roofs were installed and all of the houses were painted the same color. In 1935, the coal company went outside the town and brought in a crew to paint all of the houses white with green trim. This was quite possibly the last time the coal company painted the houses, prior to divesting themselves of ownership in 1944.

When abandoned homes had to be demolished, the crew would take their truck (stored below First Street in the company garage, which became the supply house for the coal mines in the area in 1946) to the site of the home, wrap a large, long chain around the house, attach the chain to the back of the truck and simply pull it down. After removing the nails, the crew would salvage much of the lumber from the demolished homes and store it in a building behind the carpenter’s shop on Sunnyside for future repairs or construction. At other times, the company would sell abandoned buildings to any townspeople (or outsiders) for a predetermined amount. The buyers were required to tear the building down and remove all materials from the site. One such reclamation project is rumored to be the Meadowbrook Bar/Restaurant building located just outside of Indiana. In another example, the grandstand/bleachers located at the baseball diamond were sold and the buyer used the materials to construct a single car garage on Second Street.

One job that the coal company never helped with was the removal of snow from the streets. With few cars in town, the primary objective was to provide pathways for the townspeople to travel to the doctor’s office, the post office, the company store, and for the children to attend school. The men and teenagers assembled into crews and armed with shovels, removed the snow by hand (see photo). The families along the buried streets often provided hot coffee and sandwiches to the ad hoc snow removal crews.

After the coal company divested itself of maintenance responsibilities in Heilwood, a group of concerned citizens met and formed the Citizens’ Association. Projects such as street repair, lighting, fire protection, and other necessary town needs were discussed. James Thomas was elected the first chairman of the group.

EVICTED!

The eviction letter at right reads:

May 24th, 1906

Dear Sir:

Whereas you hold posession of Lot No. 218 on which is erected a dwelling in the village of Heilwood, Pa. under lease from the Heilwood Coal Co., Lessor, dated November 1st 1905, which lease provides that it shall cease and determine immediately upon the termination of your employment by the Lessor, and that you will peaceably surrender to the Lessor possession of the aforesaid premises within five days after the termination of your employment as aforesaid.

You are hereby notified that you are no longer in the employ of the Lessor and that you are required peaceably to surrender to the Lessor possession of said premises within five days.

Yours very truly,

H.P. Dowler

Superintendent