COAL MINING: 1905-1935

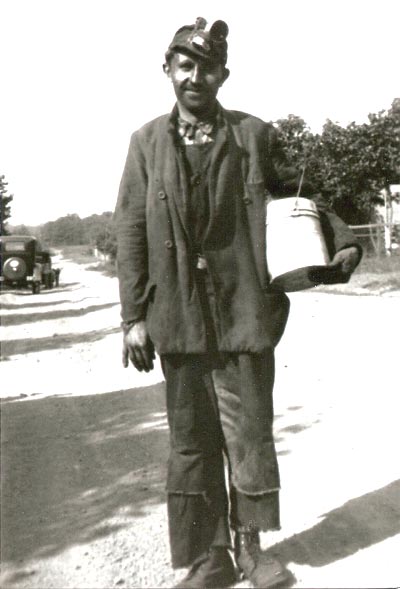

Prior to World War I, removing coal from the mines was mostly manual labor; specifically, hand-loading. A pair of miners were usually assigned a room or other specific location within a mine complex, from where they were to load their coal. At the vertical face of the coal seam, the two miners would first lie on their sides and use their picks and shovels to “undercut” a section of coal. This undercut would typically extend 3-to-4 feet into the seam, and be somewhere around 10′-to-12′ wide and 3″-to-5” high. This process could take up to three hours to complete.

Next, the miners would use an auger to strategically drill at least three holes in the face of the coal. Tamping each hole with black powder and inserting a fuse, the miners would then “shoot” the coal down, hopefully in a pile of nice lumps. They then loaded the loose coal into coal cars (usually one-ton cars), being careful not to load any rock. The miner then placed a tin check (with his identification number stamped into it) on a hook on the side of the coal car. This car was then pushed out onto the main track and taken outside to the tipple, often by mule, small pony, or electric motor. In some cases, motors were aided by steam-powered or electric hoist cables, depending on how steep the slope was at the mine entrance.

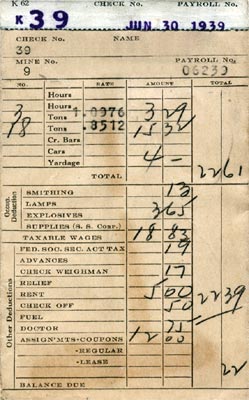

Once outside, the coal car was examined and weighed by the company “weigh boss.” This weight would determine how much the miner was paid (so much per ton). Sometimes, a weigh boss might decide that the car had too much rock, and dump it on the refuse pile without giving the miner any credit (or docking him for the amount of rock present). Or, the weigh boss could give the miner a “short weight” (i.e. less than actual weight), which would be reflected in the miner’s pay. This “company weighman” issue was one of the first things the United Mine Workers union addressed, once it came to power in the 1930s.

It must be emphasized that the miner only received pay for the actual amount of coal he sent outside the mine. All of the preliminary work done prior to loading the coal cars – the undercutting, drilling, and shooting of coal – was considered “dead work” and was not compensated. In addition, any rock that might have fallen during the undercutting process had to be removed by hand to an abandoned area, away from the face. The setting up of timbers to support the roof after the coal was removed was also considered dead work, as was the laying of track for the coal cars to ride on. Also, the tools that the miner used (picks, shovels, bars, drills, black powder, fuses) had to be purchased and maintained at no cost to the company. Miners even had to pay for the tin checks that they placed on the loaded coal cars!

Coal mining is inherently a very dangerous occupation. Miners continually faced the threats of roof collapses, explosions, and coal dust. Before there were any worker’s compensation benefits or mine safety regulations, any miner who became hurt or injured on the job faced the immediate loss of employment, and worse yet – eviction from his home.

John Brophy, the former President of the United Mine Workers, described the dilemma of the coal miner this way:

An experienced miner would often work calmly on, under conditions that would terrify a novice. This was not because he liked taking chances, but because he had to work steadily, with as little lost time as possible, to get out a good day’s production. He had to develop something like a ‘sixth sense’ that would tell him when the chances were going against him, and never miss that warning, or his career in mining would be a short one.